The 27 Club, also occasionally known as the Forever 27 Club or Club 27, is a name for a group of influential rock music artists who died at the age of 27.

The 27 Club, also occasionally known as the Forever 27 Club or Club 27, is a name for a group of influential rock music artists who died at the age of 27.

The Curse of 27 is the belief that 27 is an unlucky number due to the number of famous musicians and entertainers who have died at the age. Robert Johnson, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, Janis Joplin, Jonathan Brandis, Kurt Cobain and more recently, Amy Winehouse, are all believed to have been affected by the Curse of 27. The number 27 has been said to "follow" and bring bad luck to people. They see it random times through out the day, on the clock, on television, in phone numbers, math problems, dates, jersey numbers, etc.

The impetus for the club's creation were the deaths of Jones, Hendrix, Joplin and Morrison. Cobain, who died in 1994, was later added by some. With the exception of Joplin, there is controversy surrounding their deaths. According to the book Heavier Than Heaven, when Cobain died, his sister claimed that as a kid he would talk about how he wanted to join the 27 Club. On the fifteenth anniversary of Kurt Cobain's death, National Public Radio's Robert Smith said, "The deaths of these rock stars at the age of 27 really changed the way we look at rock music.

When legendary Blues man, Robert Johnson, was killed at the age of 27, his death is said to have spawned a curse. The legend unfolds like this: Johnson, always enamored of the Blues and desiring the ability to play guitar was, unfortunately, a mediocre talent. He disappeared for a time, during which he sold his soul to the devil by making a crossroads deal, in exchange for an unparalleled talent with the guitar. Suddenly he was a Blues master, composing songs about the crossroads and hellhounds on his trail. Johnson's ability made him popular with many (especially the ladies), but there were some who were suspicious and jealous of his talents (particularly the ladies' husbands). In 1938, he was supposedly given a bottle of wine which had been poisoned by one such jealous spouse. Johnson died a long, agonizing death. He was 27.

Robert Johnson

Since that day, it is said that many musicians - especially those of particularly high quality - would succumb to the curse and die, at the height of their careers, at the age of 27. While it is true that many musicians did, in fact, die at this age, it is hardly a magical number. Just as strong a case - if not more compelling - could be made for the age of 28. Twenty-seven by no means stands out. I have catalogued all musicians in the Archive that have died at age 27 since Robert Johnson; the list isn't nearly as long as one might think. Not including Johnson, there are 21 musicians who died at age 27 from 1938 to 2011 - that's one person roughly every three-and-a-half years. And although many of these performers were wildly famous and indisputable legends, most were supporting players in moderately successful bands.The Curse of 27

The Curse of 27 - The Forever 27 Club

Background

Moberly, born in 1846, was the tenth of fifteen children. She came from a professional background; her father, George Moberly, was the headmaster of Winchester College and later Bishop of Salisbury. In 1886 Moberly became the first Principal of a hall of residence for young women, St. Hugh's College in Oxford. It became apparent that Moberly needed someone to help run the college, and Jourdain was asked to become Moberly's assistant.

Jourdain, born in 1863, was the eldest of ten children[6] and her father, The Reverend Francis Jourdain, was the vicar of Ashbourne in Derbyshire. She was the sister of art historian Margaret Jourdain and mathematician Philip Jourdain. She went to school in Manchester, unlike most girls of the time who were educated at home. Jourdain was also the author of several textbooks, ran a school of her own, and after the incident became the vice-Principal of St. Hugh's College. Before Jourdain was appointed, it was decided that the two women should get to know one another better; Jourdain owned an apartment in Paris where she tutored English children, and so Moberly went to stay with her.

The incident

As part of several trips, they decided to visit the Palace of Versailles, as they were both unfamiliar with it. On 10 August 1901, they travelled by train to Versailles. They did not think much of the palace after touring it, so they decided to walk through the gardens to the Petit Trianon. On the way, they reached the Grand Trianon and found it was closed to the public. They travelled with a Baedeker guidebook, but the two women soon became lost after missing the turn for the main avenue, Allée des Deux Trianons. They passed this road, and entered a lane, where unknown to them they passed their destination.[9] Moberly noticed a woman shaking a white cloth out of a window and Jourdain noticed an old deserted farmhouse, outside of which was an old plough. At this point they claimed that a feeling of oppression and dreariness came over them. They then saw some men that looked like palace gardeners, who told them to go straight on. Moberly later described the men as "very dignified officials, dressed in long greyish green coats with small three-cornered hats."[12] Jourdain noticed a cottage with a woman and a girl in the doorway. The woman was holding out a jug to the girl. Jourdain described it as a "tableau vivant", a living picture, much like Madame Tussaud's waxworks. Moberly did not observe the cottage, but felt the atmosphere change. She wrote: "Everything suddenly looked unnatural, therefore unpleasant; even the trees seemed to become flat and lifeless, like wood worked in tapestry. There were no effects of light and shade, and no wind stirred the trees." The Comte de Vaudreuil was later suggested as a candidate for the man with the marked face allegedly seen by Moberly and Jourdain.

More on Ghost Haunting - Moberly–Jourdain Incident

You sit in your car, your date by your side, wondering just what you're doing here. This place is bad; everyone says so. You've heard the tales of death and spectral madmen that leap from the bushes and separate people's heads from their necks. Yet, you are here, hoping that the crickets that chirp like nervous heartbeats and echoes that sound like whispers will bring her closer to you. And you don't believe the stories anyway, right? They're just made up to scare kids away from here. But then, why is your heart racing in time with hers? Why do the echoes sound more like whispers? And why do the shadows move like inky wraiths across the walls toward your car? Surely it couldn't be real. None of it could be true. Could it?

Tales of terror, believed almost without question, are passed around from friend to friend to friend of a friend, all with the insistence that they are true. Everyone seems to know someone who has a cousin whose boyfriend's sister knows where any given event really happened. We call such stories urban legends, and more often than not, they're not true. But once in a while, the truth rears its head, and that is often the most bizarre part of the story. It becomes something of a widespread practical joke. The Bunnyman Bridge.

The Legend:

Sometime around 1905 near the Fairfax County town of Clifton, Virginia, there was a mental institution that housed the severely disturbed and criminally insane. The citizens of the county wanted no part in such a facility being so close to their homes and protested, prompting the facility to shut down and transfer the inmates to another facility in another county. The bus containing all the inmates, however, never made it to its destination. It was struck by a train, killing several of the inmates and freeing others. It took the wardens and police a few days, but in the end they managed to round up all but two.

In the weeks that followed it became obvious that the two escapees were still hanging around the vicinity as dozens, and soon hundreds, of carcasses of half-eaten rabbits were found strewn about the bridge and the surrounding areas. Another search was ordered, this one widening the search area into the woods. There, hanging in a tree, officers found Marcus Walster, one of the two escapees. He'd been gutted and dressed like a deer in much the same way the rabbits had been. It was then that they began referring to the second escapee, Douglas J. Grifon, as the "Bunnyman."

More on Urban Legend of Bunnyman Bridge

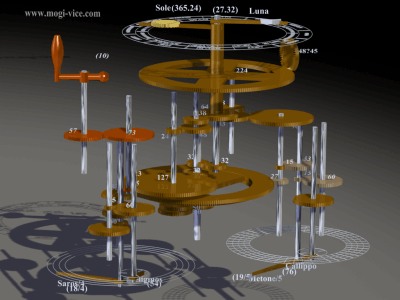

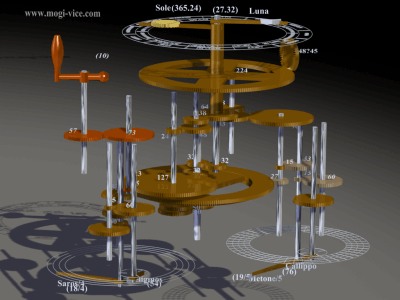

The mechanism is the oldest known complex scientific calculator. It contains many gears, and is sometimes called the first known analog computer, although its flawless manufacturing suggests that it may have had a number of undiscovered predecessors during the Hellenistic Period. It appears to be constructed upon theories of astronomy and mathematics developed by Greek astronomers and it is estimated that it was made around 150-100 BC.

Consensus among scholars is that the mechanism itself was made in the Greek-speaking world. All the instructions of the mechanism are written in Koine Greek. One hypothesis is that the device was constructed at an academy founded by the Stoic philosopher Posidonius on the Greek island of Rhodes, which at the time was known as a center of astronomy and mechanical engineering, and that perhaps the astronomer Hipparchus was the engineer who designed it since it contains a lunar mechanism which uses Hipparchus's theory for the motion of the Moon. However, the most recent findings of The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, as published in the July 31, 2008, edition of Nature alternatively suggest that the concept for the mechanism originated in the colonies of Corinth, which might imply a connection with Archimedes.

Nothing like this instrument is preserved elsewhere. Nothing comparable to it is known. from any ancient scientific text or literary allusion. On the contrary, from all that we know of science and technology in the Hellenistic Age we should have felt that such a device could not exist. Some historians have suggested that the Greeks were not interested in experiment because of a contempt-perhaps induced by the existence of the institution of slavery-for manual labor. On the other hand it has long been recognized that in abstract mathematics and in mathematical astronomy they were no beginners but rather "fellows of another college" who reached great heights of sophistication. Many of the Greek scientific devices known to us from written descriptions show much mathematical ingenuity, but in all cases the purely mechanical part of the design seems relatively crude. Gearing was clearly known to the Greeks, but it was used only in relatively simple applications. They employed pairs of gears to change angular speed or mechanical ad- vantage, or to apply power through a right angle, as in the water-driven mill.

Even the most complex mechanical devices described by the ancient writers Hero of Alexandria and Vitruvius contained only simple gearing. For example, the taximeter used by the Greeks to measure the distance travelled by the wheels of a carriage employed only pairs of gears (or gears and worms) to achieve the necessary ratio of movement. It could be argued that if the Greeks knew the principle of gearing, they should have had no difficulty in constructing mechanisms as complex as epicyclic gears. We now know from the fragments in the National Museum that the Greeks did make such mechanisms, but the knowledge is so unexpected that some scholars at first thought that the fragments must belong to some more modern device.

More on Antikythera Mechanism

Stigmata (singular stigma) are bodily marks, sores, or sensations of pain in locations corresponding to the crucifixion wounds of Jesus, such as the hands and feet. In some cases, rope marks on the wrists have accompanied the wounds on the hands.

The term originates from the line at the end of Saint Paul's Letter to the Galatians where he says, "I bear on my body the marks of Jesus." Stigmata is the plural of the Greek word st??µa stigma, meaning a mark or brand such as might have been used for identification of an animal or slave. An individual bearing stigmata is referred to as a stigmatic or a stigmatist.

Stigmata are primarily associated with the Roman Catholic faith. Many reported stigmatics are members of Catholic religious orders. St. Francis of Assisi was the first recorded stigmatic in Christian history. For over fifty years Padre Pio of Pietrelcina reported stigmata which were studied by several 20th century physicians, whose independence from the Church is not known. The observations were reportedly unexplainable and the wounds never became infected.

A high percentage (perhaps over 80%) of all stigmatics are women. In his Stigmata: A Medieval Phenomenon in a Modern Age, Edward Harrison suggests that there is no single mechanism whereby the marks of stigmata were produced.

What is it ?

Strictly speaking, stigmata are marks on someone’s body that correspond to the crucifixion wounds of Jesus as stated in Christianity’s bible—with particular emphasis on marks that occur on the person’s hands or feet. Stigmata is actually the plural form of a Greek word “stigma” which literally translates as a brand or mark that was used in the identification of a domesticated animal or slave. The word stigmata as applied to marks or wounds associated with those of Jesus actually comes from Paul’s letter to the Galatians at the end line of the writing where he stays that he bears “on (his) body the marks of Jesus.” The reported cases of stigmata show some, a few, or all five of the “holy wounds” that were inflicted on Jesus according to writing of his crucifixion in the bible, which include a wound in the side of a torso from a lance and ones in the hands and feet from nails.

More on Stigmata

The 27 Club, also occasionally known as the Forever 27 Club or Club 27, is a name for a group of influential rock music artists who died at the age of 27.

The 27 Club, also occasionally known as the Forever 27 Club or Club 27, is a name for a group of influential rock music artists who died at the age of 27.